How to Accept Loneliness

Accepting Loneliness: A Guide to Embracing Solitude[edit | edit source]

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Loneliness is a universal human experience – virtually everyone feels alone at times. In today’s fast-paced, hyper-connected world, the ache of loneliness can be especially pronounced. Yet being alone doesn’t have to be painful; learning to accept loneliness and even embrace solitude can transform those empty moments into opportunities for growth and peace. This guide offers practical strategies, psychological insights, and philosophical perspectives to help you not only cope with loneliness, but also find value in it. We’ll explore self-care practices, the psychology behind loneliness, wisdom from philosophies like existentialism and Buddhism, ways to build emotional resilience, and how to distinguish healthy solitude from harmful isolation. By the end, you’ll have a roadmap for turning loneliness into a path of self-discovery and inner strength.

Understanding Loneliness: Causes and Impact[edit | edit source]

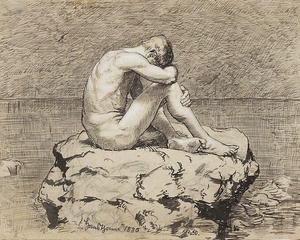

(Pema Chödrön’s Six Kinds of Loneliness) Figure: “Loneliness” (1880) by Hans Thoma. A 19th-century depiction of isolation’s weight – a lone individual curled up on a barren rock. Loneliness is a subjective feeling of being isolated or disconnected, which can occur even if people are physically around us. Loneliness has been defined by psychologists as “the discrepancy between one’s desired and actual social connection” (Coping With Loneliness (Part 1): Look Inward | USU). In other words, it’s the gap between how much closeness or companionship you want and what you actually have. This gap can arise for many reasons – you might have lost a relationship or loved one, moved to a new place, experienced social rejection or marginalization, or be facing health or mental health challenges that make connecting difficult (Coping With Loneliness (Part 1): Look Inward | USU). Sometimes the feeling is acute after a major life change; other times it’s a chronic sense of being unseen or not understood. Researchers note that loneliness can take different forms, such as intimate loneliness (lacking a close confidant), relational loneliness (lacking friendships or family ties), or collective loneliness (lacking a sense of community or group belonging) (Coping With Loneliness (Part 1): Look Inward | USU). Recognizing what type of loneliness you feel can be a first step in addressing it – whether you miss one special connection or a network of support.

It’s important to remember that loneliness is not the same as simply being alone. Loneliness is a distressing subjective experience – the pain of feeling isolated – whereas being alone (often termed social isolation) is an objective state of having few people around (Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation). You can feel deeply lonely in a crowd, or feel perfectly content in solitude. This subjective nature means our mindset matters greatly: two people with the same situation can feel differently based on how they interpret being alone. When loneliness is persistent and unresolved, it can take a toll on our well-being. Emotionally, chronic loneliness often feeds sadness, anxiety, low self-esteem, and can even lead to depression (Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation). The stress of loneliness triggers our brain’s threat response – we may feel tense and hyper-vigilant or, conversely, numb and exhausted. Over time, this stress can impact the body as well. Studies have found that a lack of social connection carries serious health risks – long-term loneliness has been linked to higher risks of heart disease and stroke, and can increase the risk of premature death as much as smoking 15 cigarettes a day (Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation) (Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation). In older adults, loneliness is associated with cognitive decline and dementia (Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation). These findings highlight that loneliness isn’t a trivial inconvenience but a significant factor in mental and physical health. Knowing this, it becomes even more important to find healthy ways to cope with and ultimately accept loneliness. The encouraging news is that by understanding the psychology of loneliness and approaching it with the right strategies, you can alleviate much of its sting and build resilience against it.

Practical Techniques for Coping with Loneliness[edit | edit source]

While loneliness can feel overwhelming, there are many practical techniques you can use in daily life to cope with those feelings and cultivate a sense of comfort with being on your own. Here are some effective strategies:

- Practice Self-Care and Self-Compassion: Tending to your own needs is crucial when you feel lonely. Make sure you are eating well, getting enough sleep, and staying physically active – basic self-care helps stabilize your mood. Just as important is emotional self-care: pay attention to your inner dialogue. Lonely periods can trigger harsh self-criticism (“No one likes me” or “I deserve to be alone”), which only makes you feel worse. Counter this with self-compassion. Treat yourself with the same kindness you’d offer a good friend. Notice negative self-talk and gently reframe it – for instance, if you catch yourself thinking “I’m so unlovable,” you might remind yourself, “Feeling lonely doesn’t mean I’m unlovable. I have value.” Practicing this kind of self-compassion can break the cycle of negativity. In fact, mental health experts note that being aware of negative self-talk and replacing it with compassion helps diminish loneliness and builds a healthier self-image (Coping With Loneliness (Part 1): Look Inward | USU). Befriend yourself: take yourself out for a nice coffee, run a warm bath, or engage in activities you enjoy. By doing so, you reinforce that you deserve care and enjoyment, even if no one else is around at the moment.

- Engage in Hobbies and Creative Outlets: Using alone time to dive into hobbies or creative interests not only distracts from loneliness – it can make your alone time rewarding. What activities make you feel “in the zone” or bring you joy? It could be reading novels, playing video games, cooking, gardening, crafting, making music, or learning a new skill. Losing yourself in a creative project or an engaging hobby provides a sense of purpose and accomplishment. Psychologists note that creative pursuits (like painting, writing, or playing an instrument) can be therapeutic and give you a feeling of achievement, which boosts your mood (Strategies for navigating loneliness and isolation). Even solo physical activities like exercising, hiking, or yoga can lift your spirits by releasing endorphins and giving you a healthy routine. Try scheduling a little time each day for an activity you genuinely want to do – this gives you something to look forward to when you’re alone, turning what could be empty hours into productive or fun sessions. Over time, you may start cherishing these solo hobbies as special “me time” rather than fearing them.

- Keep a Journal: Journaling is a powerful tool for coping with loneliness. When you feel isolated, you likely have a storm of thoughts and feelings swirling inside. Putting them down on paper (or a digital notebook) helps in several ways. First, it provides an emotional release – venting onto the page can relieve some of the weight on your chest. Second, it brings clarity. By writing about your loneliness, you start to understand why you feel the way you do, and you might spot patterns or triggers. For example, you might notice you feel loneliest in the evenings, or after scrolling social media. These insights can guide you to adjust your routine or mindset. Studies have found that keeping a journal can help you process your thoughts and emotions, providing valuable insight into your feelings and behaviors (Strategies for navigating loneliness and isolation). You can try different forms of journaling: free-writing whatever comes to mind, recording a daily log of your moods, or using prompts (like “Today, loneliness feels like…”, “What I wish I could tell someone is…”). You might also include gratitude journaling – writing a few things you’re thankful for each day. This can shift your focus toward the positive and counteract the brain’s tendency to fixate on what’s missing. Over time, a journal becomes a safe space where you express yourself honestly. Re-reading past entries can show you how you’ve grown and remind you that feelings come and go.

- Mindfulness and Meditation: Practicing mindfulness is about learning to be present with whatever you’re experiencing, without judgment. Rather than immediately trying to escape feelings of loneliness, mindfulness encourages you to gently face them and let them pass. This might sound difficult, but it can significantly reduce the suffering associated with loneliness. Mindfulness is “awareness that arises through paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment, non-judgmentally,” as expert Jon Kabat-Zinn defines it (Coping With Loneliness (Part 1): Look Inward | USU). When you practice mindfulness, you train yourself not to catastrophize the feeling of being alone or label it as something wrong with you. You simply notice, “I feel lonely right now,” and recognize it as a passing mental state, not a permanent identity. Techniques like breathing exercises, body scans, or guided meditation can ground you in the present. In fact, research has shown that mindfulness and meditation can directly help ease loneliness. In one study, participants who did a daily guided meditation reported reduced loneliness and increased social connection (Coping With Loneliness (Part 1): Look Inward | USU). Meditation helps by calming the anxious thoughts (“I’ll always be alone”) and creating a sense of inner peace. Even informal mindfulness – like taking a slow, attentive walk in nature or eating a meal in silence focusing on the taste – can pull you out of rumination. Over time, mindfulness builds your capacity to sit with solitude without feeling panicked or sad. It teaches the valuable skill of acceptance: you learn to coexist with feelings like loneliness without fighting them. This often makes those feelings diminish, since much of loneliness’s pain comes from our resistance to it. Consider trying a simple practice like sitting quietly for 5–10 minutes, eyes closed, focusing on your breath. When feelings of loneliness or thoughts arise, note them (“thinking” or “feeling lonely”) and gently return your focus to breathing. This trains your mind that loneliness is a feeling you can observe and get through, not an enemy that controls you. Apps or online videos can guide you if you’re new to meditation. With regular practice, mindfulness can foster a steadier, more resilient mindset in the face of alone-ness.

- Reach Out (in Moderation): While this guide is about accepting loneliness, coping doesn’t mean you must isolate completely. Sometimes a small dose of human connection can remind you that you’re not alone in the world. Consider reaching out to a friend or family member with a text or call, even if just to say hello. If you don’t have someone close, joining an online community or forum around an interest, or attending a casual meetup (like a book club or hobby class), can provide low-pressure social contact. The goal here isn’t to instantly cure loneliness with others’ company – it’s to give yourself balance. Think of social interaction as similar to sunlight: even if you’re living in a period of solitude, you still need a bit of connection to stay emotionally healthy. If you’ve been isolating a lot, push yourself gently to interact in small ways. Volunteer work or helping someone else can also be incredibly fulfilling; focusing on others takes you out of your own head and can reduce the sting of loneliness. Remember, accepting loneliness doesn’t mean swearing off all companionship – it means not relying on it for your happiness. By occasionally connecting with others (or simply being around people at a park or café), you reinforce that the world is still there for you, even as you cultivate strength on your own.

Each of these techniques – caring for yourself, finding hobbies, journaling, mindfulness, and balanced social contact – is a way of actively coping with loneliness. They help you take loneliness from a passive, painful state to an active choice of how to spend your time. Try combining several strategies: for example, you might start your day with a short meditation, plan a hobby activity in the afternoon, and journal in the evening. As you practice these, you’ll likely find that loneliness becomes more manageable. You may even start to appreciate the freedom and self-discovery that comes with being on your own. In the next sections, we’ll delve deeper into how shifting your mindset and perspective on loneliness can further transform it into something meaningful.

Philosophical Perspectives on Solitude[edit | edit source]

Throughout history, philosophers and spiritual traditions have grappled with loneliness and the value of solitude. By looking at loneliness through a philosophical lens, we can find wisdom that reframes being alone as an opportunity rather than a deficiency. Here, we draw on a few schools of thought – Existentialism, Buddhism, and Stoicism – for insights into solitude and how to accept it.

(File:Caspar David Friedrich - Wanderer above the sea of fog.jpg - Wikimedia Commons) Figure: Embracing Solitude. Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, a famous 1818 painting by Caspar David Friedrich, depicts a lone figure standing high above a foggy landscape. Rather than conveying despair, the scene suggests contemplation, self-reflection, and even empowerment in solitude. Philosophers and spiritual teachers throughout time have often praised the ability to be alone. In their view, solitude can be a path to clarity and inner strength.

Existentialism: The Human Condition of Aloneness[edit | edit source]

Existentialist thinkers confront loneliness head-on, seeing it as an inherent part of the human condition. In existential philosophy (associated with figures like Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, and Albert Camus), each individual ultimately stands alone to create meaning in their life. There is an idea of “existential isolation” – the realization that no matter how close we are to others, we each experience life in our own unique way and ultimately face existence (and death) alone (Existential Isolation Is Key to Healthy Relationships | Psychology Today). While this might sound bleak, existentialists actually use it as a call to authenticity and connection. The famed psychotherapist Irvin Yalom noted that when we confront our fundamental aloneness, it can lead us to relate to others in a more genuine way. Instead of desperately clinging to people out of fear of being alone, we choose to be with them freely and authentically. In fact, “just as existentialists believe one who confronts his mortality will live a fuller life, existentialists believe one must confront their aloneness in order to have healthy relationships.” (Existential Isolation Is Key to Healthy Relationships | Psychology Today) Rather than avoiding the feeling of loneliness through constant distraction, they suggest we accept it, even sit with the discomfort of it, to understand ourselves better. By doing so, we can approach relationships from wholeness rather than neediness. Sartre famously quipped, “If you are lonely when you’re alone, you are in bad company,” implying that being comfortable with your own company is crucial – it’s about making peace with yourself so that solitude isn’t scary. In existentialism, accepting loneliness is an opportunity to define your own values and meaning. With no one else around, who are you? What do you care about? These questions, though tough, can lead to profound personal insights and a stronger sense of self. The existential perspective encourages you to see solitude as a chance to become more authentically you – to find inner freedom and purpose that isn’t dependent on others. Paradoxically, by finding meaning in solitude, you become less lonely because you feel connected to your own life. Loneliness then transforms from an enemy into a teacher – guiding you to deeper self-understanding and, ultimately, richer connections when you do engage with others.

Buddhism: Mindfulness and Non-Attachment to Emotions[edit | edit source]

Buddhist philosophy offers a compassionate approach to dealing with loneliness. In Buddhism, all emotions – including loneliness – are seen as temporary states that we shouldn’t cling to or push away. A core idea is acceptance and non-attachment: suffering increases when we desperately resist or grasp at feelings. Instead, Buddhism encourages us to mindfully observe our loneliness, without judgment, and let it pass like a cloud in the sky. Buddhist teachers even speak about cultivating a positive form of solitude. The Buddhist nun Pema Chödrön coined the term “cool loneliness” to describe a state of open, relaxed aloneness. She explains that usually we experience loneliness as “hot” – a restless, desperate feeling where we frantically seek something to fill the void (Pema Chödrön’s Six Kinds of Loneliness). But if we can refrain from automatically trying to escape our loneliness – if we “sit in the middle” of that discomfort – it can cool down into something different. In her words, “when we can rest in the middle, we begin to have a nonthreatening relationship with loneliness, a relaxing and cooling loneliness that completely turns our usual fearful patterns upside down.” (Pema Chödrön’s Six Kinds of Loneliness) This nonthreatening relationship with loneliness comes from realizing that feeling lonely won’t actually harm us; it’s just a feeling. Through meditation and mindfulness practice, we train to stay present even with painful emotions. For example, a mindfulness exercise might be to sit quietly and actually feel the sensations of loneliness in your body – maybe a tight chest or an empty ache – and notice the thoughts that come with it, but resist the urge to run away or label it as something bad. As you build this “muscle” of sitting with loneliness, you may notice it loses some of its heat and power over you. “One can be lonely and not be tossed away by it,” as Zen master Katagiri Roshi said (Pema Chödrön’s Six Kinds of Loneliness). In Buddhism, another key principle is interconnectedness – even when alone, we are still connected to all other beings. Thich Nhat Hanh, a renowned Buddhist monk, often taught that when we are lonely, we can look deeply and see that we are actually part of a larger whole (we rely on the earth, water, food grown by farmers, the sunshine – we are never truly isolated from life). This perspective can bring comfort, making loneliness feel less like a personal failing and more like a universal experience. Additionally, Buddhists value solitude for spiritual growth; many monks intentionally spend long periods alone meditating. They view solitude as a time to cultivate wisdom and compassion for oneself and others. Following this example, you might treat your lonely times as retreats for your mind – periods to practice meditation, reflect on life, and develop inner calm. The Buddhist approach reassures us that loneliness is not a permanent truth about you – it’s a passing feeling. By neither fighting it nor feeding it, you allow loneliness to transform into peace. Over time, this mindset of acceptance can greatly reduce the fear of being alone. You come to see solitude as fertile ground for insight and tranquility, rather than a barren wasteland of abandonment.

Stoicism: Inner Strength and Self-Reliance[edit | edit source]

The Stoic philosophers of ancient Greece and Rome (like Seneca, Epictetus, and Marcus Aurelius) also had valuable advice on being alone. Stoicism teaches the development of inner strength, resilience, and focusing on what is in our control. When it comes to loneliness, Stoicism reminds us that while we can’t always control whether others are around or understand us, we can control our own mindset and actions. The Stoics believed that a wise person is content with themselves and can find peace in solitude. Seneca, for example, wrote, “Nothing, to my way of thinking, is a better proof of a well-ordered mind than a man’s ability to stop just where he is and pass some time in his own company.” (How Do Stoics Deal With Lonliness? - Orion Philosophy) In other words, being able to be alone with yourself is a sign of emotional maturity and stability. If you can enjoy or at least be at peace in your own company, it shows you have cultivated a strong mind. Stoicism doesn’t suggest that we should shun society – on the contrary, Stoics valued friendship and community – but it emphasizes that we shouldn’t be dependent on external things for our inner wellbeing. Epictetus taught that we should distinguish between what is within our power and what is not. Our own opinions, thoughts, and choices are up to us; other people’s actions or life circumstances are not (How Do Stoics Deal With Lonliness? - Orion Philosophy). Applying this to loneliness: you cannot fully control when friends move away, or how others behave, or whether you have a romantic partner at a given time. But you can control how you respond to being alone. You can choose to use solitude as a time to read, learn, and grow, rather than letting it sour into self-pity. Stoicism encourages using loneliness as a signal for self-improvement – if you feel lacking in companionship, you might work on becoming an even better companion to yourself. This could mean educating yourself, honing a talent, or strengthening your virtues (patience, courage, humility). By doing so, you not only ease the loneliness through activity, but you become the kind of person who is content and confident alone, which is incredibly empowering. Stoics also practiced negative visualization – imagining worst-case scenarios – to appreciate what they have. In your case, imagining being truly isolated forever might make you appreciate the connections you do have (however few) and motivate you to nurture them, while still knowing you could endure even if those connections are sparse. Another Stoic strategy is reframing: instead of “I have to be alone tonight,” a Stoic might think “I get to be alone tonight, which means I’m free to do anything I choose.” Notice how that shift turns solitude into a freedom rather than a jail. Modern Stoic writers point out that the only person you’re with 100% of the time is yourself – so it’s necessary for a resilient life to learn to be comfortable in your own company (How Do Stoics Deal With Lonliness? - Orion Philosophy). If being alone makes us uneasy, we’ll constantly seek distractions (endless social media, TV, or unhealthy relationships) to avoid facing ourselves (How Do Stoics Deal With Lonliness? - Orion Philosophy). Stoicism invites us to stop running away. By practicing gratitude for our present moment and focusing on our own actions, we can maintain peace of mind even when alone. The Stoic approach, much like the others, transforms loneliness into an exercise in inner strength: every moment of solitude is a chance to sharpen your character and self-sufficiency. When you succeed in doing that, loneliness loses its fangs – you know you’re capable of standing strong, with or without others around.

Building Emotional Resilience and Self-Acceptance[edit | edit source]

Emotional resilience is the ability to withstand and bounce back from life’s difficulties, and it’s a quality that can be developed. When facing loneliness, building resilience and self-acceptance will help you endure the tough moments and emerge stronger. Here are some strategies to cultivate these traits:

- Acknowledge and Accept Your Feelings: Rather than denying that you feel lonely or beating yourself up for it, acknowledge it honestly. It’s okay to feel lonely – it doesn’t mean you’re weak or broken, it means you’re human. Acceptance is powerful. Remind yourself that emotions come in waves; loneliness might be here today, but it can ease tomorrow. By saying “Yes, I feel lonely right now, and that’s alright,” you reduce the extra layer of suffering that comes from feeling bad about feeling bad. Psychologically, this is known to help – accepting emotions as they are can actually lessen their intensity (Coping With Loneliness (Part 1): Look Inward | USU). In one study, people who accepted their loneliness (instead of constantly wishing their social situation were different) experienced less distress and more gratitude for what connections they did have (Coping With Loneliness (Part 1): Look Inward | USU). Acceptance doesn’t mean you’ll feel lonely forever; it simply means you stop wasting energy on fighting the feeling. This frees up mental space to work on positive action (like the coping strategies above) and to notice the bits of goodness in your life that loneliness was obscuring. Try this: the next time a wave of loneliness hits, take a deep breath and mentally say, “I feel lonely, and I accept this feeling in this moment.” You might be surprised at how it softens the pain.

- Challenge Your Inner Critic: Loneliness can distort our self-perception. You might start to believe you’re lonely because something is wrong with you – “I’m not fun enough, pretty enough, successful enough,” etc. These are conclusions drawn by an inner critic when we’re emotionally low. Strengthening your emotional resilience means not letting that critic run the show unchecked. When a self-deprecating thought pops up, practice cognitive reframing. Ask yourself: Is this thought factual? Is there evidence against it? For example, you may think, “I have no friends because I’m too weird.” Counter that by recalling people who have appreciated your quirks, or times you had good interactions. Replace harsh judgments with more compassionate and realistic statements: “I might feel different, but everyone is unique in their own way – the right people will appreciate me.” This kind of positive self-talk is not about lying to yourself; it’s about giving yourself the benefit of the doubt and not assuming the worst. Over time, consistently replacing self-criticism with affirmations or kinder thoughts builds self-acceptance. It’s like re-wiring your brain to see yourself as worthy of love and friendship. Therapists often recommend writing a list of your good qualities or things you’ve accomplished and reviewing it when you feel down on yourself. By affirming your own value, you become emotionally stronger and less dependent on external validation. In essence, become your own cheerleader. Resilience grows when you have your own back.

- Practice Gratitude and Reframe Perspective: When we feel lonely, our attention zooms in on what we lack. A resilient mind learns to also recognize what is present. Take a moment each day to note a few things you’re grateful for or that went well – no matter how small. It could be as simple as, “I enjoyed my cup of coffee this morning,” or “The sunset was beautiful.” This isn’t to deny loneliness, but to widen your perspective so it doesn’t overshadow everything. Research shows that gratitude can improve mood and overall outlook on life. It reminds you that life has pieces of joy and connection (you might appreciate a kind message from a colleague, or the companionship of a pet, or your own health). Gratitude shifts your focus from scarcity to abundance. Additionally, try reframing loneliness as solitude (as we’ll discuss in the next section on growth). Instead of viewing time alone as “lonely emptiness,” call it “quiet solitude” or “me time.” Simply changing the label in your mind can change how it feels. For example, when alone on a Saturday, consciously think, “I have the freedom to do anything I want right now.” This reframing turns a negative into a potential positive. Emotional resilience involves these mental shifts – seeing challenges through a different lens. You can even reframe loneliness as a training ground for strength: “This is hard, but it’s teaching me to be stronger and more self-reliant. I’ll emerge from this more resilient.” Believing there is meaning or benefit in your struggle makes it easier to handle.

- Build Small Routines and Goals: Loneliness can sap motivation – days can feel aimless when you don’t have social plans. To counter this, give your days structure. Set small daily goals or create routines that give you a sense of stability. It might be a morning walk, an afternoon reading hour, or an evening workout. Having a routine gives a rhythm to your solitude and prevents you from feeling lost in unstructured time. Setting achievable goals (like finishing a chapter of a book, cleaning one part of your room, or learning a new recipe) provides little hits of accomplishment. Each time you meet a goal, you reinforce a feeling of competence (“I did that!”) which boosts self-esteem. Over time, these small wins build up your confidence that you can handle life on your own. You start seeing yourself as capable and proactive, rather than a passive victim of loneliness. This mindset is the essence of resilience. Remember to reward yourself for sticking to routines or achieving goals – celebrate it, even if quietly. This conditions your mind to feel proud and content in solitude.

- Seek Support When Needed (It’s Not Weakness): Being resilient doesn’t mean never seeking help. In fact, resilient people know when to reach out. If you’re struggling with intense loneliness or it’s leading to depression, talking to a therapist or counselor can provide relief and coping tools. Sometimes just voicing your feelings to an impartial, supportive listener can lighten the burden. There are also support groups (in person or online) where you can share experiences with others who feel the same – this can create a sense of understanding and community. If therapy isn’t accessible, even confiding in a trusted friend or family member about your feelings can help. You might fear being seen as a burden, but consider how you would feel if a friend came to you feeling lonely – most likely, you’d be glad they trusted you and you’d want to be there for them. Others likely feel the same about you. Importantly, seeking help does not mean you’ve failed at being alone. You’re allowed to need human connection; it’s wired into us. Think of professional help or support as tools to build resilience, just like exercise is a tool to build physical strength. By caring for your mental health in this way, you’re equipping yourself to handle loneliness better long-term. Self-acceptance also means accepting when you need a bit of external help. There is no shame in it – quite the opposite, it’s a courageous and proactive step.

Building resilience and self-acceptance is a gradual process. Be patient with yourself. You might still have hard days – that’s normal. But as you practice acknowledging your feelings, talking to yourself kindly, keeping perspective, and taking positive actions, you’ll likely notice that loneliness becomes less threatening. You’ll bounce back faster from its attacks. You’ll trust in your ability to handle solitude, and that confidence will be like an emotional armor. Self-acceptance will also grow; you’ll start to feel comfortable in your own skin, whether alone or with others. This combination of resilience and self-acceptance is ultimately what it means to truly accept loneliness – not as a dreaded fate, but as one experience among many that you can navigate and even use for your benefit.

Turning Loneliness into Personal Growth and Self-Discovery[edit | edit source]

One of the most powerful shifts you can make is to start seeing loneliness not just as something to endure, but as an opportunity for personal growth. Many great artists, writers, and thinkers have used periods of solitude to cultivate creativity, insight, and a stronger sense of self. You too can transform lonely times into fruitful times by changing how you approach them. Instead of thinking of loneliness as wasted time or just emptiness, reframe it as solitude – quality time with yourself, which is just as important as time spent with others (if not more so). When you are alone, you have the freedom to explore things without outside judgments or distractions. This freedom, used wisely, can lead to significant self-discovery.

Consider some of the gifts of solitude that you can tap into:

- Self-Reflection and Understanding: Busy social lives can sometimes drown out our inner voice. Solitude gives you the chance to tune into you. Use lonely moments to ask yourself meaningful questions: What do I truly enjoy? What values matter most to me? What do I want to accomplish in life? Reflect on your experiences and feelings. You might write down insights in your journal or simply contemplate during a quiet evening. Without others’ opinions in the mix, you may arrive at original conclusions about who you are and what you want. This kind of self-knowledge is incredibly valuable. It guides your future decisions and strengthens your identity. Solitude, as researchers have found, can lead to greater self-understanding and even life satisfaction (Coping With Loneliness (Part 1): Look Inward | USU). Think of it as having a deep conversation with yourself – initially awkward, perhaps, but ultimately enlightening.

- Creativity and Passion Projects: If you have a creative hobby or a project you’ve always wanted to start, loneliness can be the catalyst to dive in. When alone, you have fewer distractions and more space to let your imagination roam. Whether it’s writing poetry, coding an app, painting, playing guitar, or any creative outlet – solitude is often the fertile soil for creativity to bloom. The author J.K. Rowling noted that the idea for Harry Potter first came to her during a long train ride when she was alone with her thoughts. Many innovators and artists do their best work in solitude, precisely because they can concentrate deeply. You don’t have to create a masterpiece for solitude to be worthwhile; even small creative acts are fulfilling. Maybe you sketch in a notebook for fun or try new recipes in the kitchen – whatever makes you feel expressive. The act of creating something can replace feelings of loneliness with a sense of purpose and joy. It’s hard to feel “useless” when you just wrote a chapter of a story or built a birdhouse by yourself – you have a product of your solitary time that you can be proud of. Next time you find yourself with a lonely Sunday afternoon, consider it an invitation to create or learn something new.

- Skill-Building and Learning: Likewise, you can use alone time to develop skills or knowledge. Always wanted to speak Italian, play the piano, or understand coding? There are countless online resources and books for self-learning. Pick something you’re curious about and make it a project. Not only will you distract yourself from loneliness, but you’ll come away with new abilities. Learning is inherently rewarding – it proves that you can change and grow any time in life. Set small goals, like “Practice guitar 30 minutes today” or “Complete one module of an online course.” As you progress, you’ll gain confidence. Importantly, you’ll start to appreciate solitude as productive time. Instead of, “I’m alone again tonight…,” you might think, “Great, I can work on my photography skills tonight.” This mindset turns loneliness on its head: rather than a sign of stagnation, alone time becomes a chance for advancement. Over weeks and months, you might be amazed at how much you’ve learned or created during periods that once felt empty. This builds a sense of independence too – you realize you don’t always need a class or a group to learn; you are capable of guiding your own growth.

- Reconnecting with Nature or Spirituality: Solitude and nature often go hand in hand. A simple walk in the park or a hike alone can be deeply nourishing. In nature, many people report feeling connected to something larger – the rhythms of the earth, the beauty of life around them – which can ease the sting of human loneliness. If you have access to a safe outdoor space, try spending time there by yourself. Notice details: the sway of trees, the sound of birds, the feel of the breeze. This mindful presence in nature can instill calm and wonder. It reminds us that we are part of a bigger tapestry of life. Some find that solitary time in nature borders on the spiritual – it can be a space to pray, meditate, or simply experience awe. Similarly, if you have a spiritual faith or practice, solitude is a perfect time to delve into it. Through prayer, meditation, or reading spiritual texts, you may find comfort and a sense of companionship with the divine or the universe. Spiritual figures from Jesus to Buddha sought solitude in deserts and forests to attain clarity and strength. You might not be looking for enlightenment on a mountaintop, but a quiet moment gazing at a starry sky can certainly put your worries in perspective and make you feel less alone in a cosmic sense. The key is to use solitude to nurture your soul – whatever that means to you personally.

- Planning and Personal Goals: Finally, lonely moments can be great for life planning. Take stock of where you are and where you want to go. Perhaps create a list of personal goals or a bucket list of experiences you’d like to have. Without the noise of daily chatter, you might visualize your future more clearly. What steps could you take, even small ones, towards those goals? Maybe you want to get in better shape, or save money for travel, or switch careers. Solitude grants you the time to strategize and self-motivate. You could outline a fitness routine, research vacation spots, or study for a career-related exam in your alone time. Setting and pursuing goals gives your life direction and meaning, which counteracts the aimlessness that makes loneliness harder. It also fills you with a sense of progress – you’re not “just alone,” you’re actively moving forward on something. Each step you take towards a goal is something to celebrate internally, and it reinforces that being alone can be constructive. You’re essentially becoming the architect of your own life during these solitary periods.

When you start leveraging solitude for self-reflection, creativity, learning, nature, or planning, you’ll likely notice a shift: the time you dreaded as “lonely” starts feeling rich and even necessary. You might begin to cherish your solo morning run or your quiet art afternoons. This doesn’t mean you’ll never desire company – humans are social creatures after all – but it means you’ve expanded your perspective. You now see that solitude has benefits that companionship doesn’t, just as friends provide things you can’t get alone. Your life becomes more balanced because you can derive fulfillment both from others and from yourself.

Research has indeed found many positive outcomes from time spent alone by choice. Psychologists note that solitude (when approached with a positive mindset) can lead to rejuvenation, creativity, and increased life satisfaction (Coping With Loneliness (Part 1): Look Inward | USU). By reframing loneliness as “me time,” you transform it from a void to an oasis. Each stretch of solitude is a chance to deepen your relationship with yourself and to do things that genuinely matter to you. In this way, loneliness becomes a catalyst for growth. It teaches you to find contentment within, to ignite your own inspiration, and to value your own company. Those are lessons that will serve you for a lifetime, in every realm of life.

Healthy Solitude vs. Harmful Isolation[edit | edit source]

As you work on accepting loneliness and making the most of solitude, it’s important to recognize the difference between healthy solitude and harmful isolation. Outwardly they might look similar (both involve being alone), but the inner experience and outcomes are very different. Understanding this distinction will help you gauge whether your alone time is benefiting you or if it’s veering into unhealthy territory.

Healthy solitude is a positive, restorative state of being alone. It’s usually chosen or at least accepted willingly. In healthy solitude, you still feel connected – perhaps to yourself, to nature, to your interests, or to loved ones even if they’re not present. You use the time alone for rest, reflection, creativity, or personal activities (like those described above). You generally feel at peace with yourself. Importantly, healthy solitude still allows for the possibility of social interaction; you aren’t cut off, you’re just comfortable being with you. Think of healthy solitude as the enriching “me time” that leaves you recharged rather than depleted. As one poet put it succinctly, loneliness is the poverty of self, while solitude is the richness of self – in solitude, you feel enriched and enough, not lacking. When you finish a period of healthy solitude, you typically have energy or insights to bring back to your relationships. For example, after a weekend spent happily puttering on your own projects, you might find you enjoy socializing on Monday even more, because you have new thoughts and a rebalanced mind. Solitude also tends to feel time-limited or voluntary – you know you can call a friend tomorrow or go back to work in a couple days; you’re not trapped indefinitely alone, and that knowledge makes the solitude feel safe. People experiencing healthy solitude often report feelings of calm, clarity, self-confidence, and creativity. You might even find that you sometimes crave solitude – a sign that it’s become a nourishing part of your life.

Harmful isolation, on the other hand, is a negative state that can be detrimental to your well-being. Isolation in this sense is often unwanted – it’s the loneliness that feels imposed, not chosen. You might be physically alone a lot and feeling emotionally alone even when you try to connect. Harmful isolation tends to involve a sense of despair or resignation (“I have nobody. I’ll always be alone.”). Rather than using alone time productively, in harmful isolation one might withdraw further, ruminate on grievances or self-blame, and neglect self-care. For instance, someone in a state of harmful isolation might stop putting effort into their appearance, disrupt their sleep schedule, or abandon hobbies, because they feel there’s no point if they’re doing it alone. Isolation becomes a vicious cycle: you feel lonely, you withdraw or others withdraw from you, which makes you feel even more lonely and unworthy, and so on. This is the kind of loneliness that correlates with depression, anxiety, and poor health we discussed earlier. It’s essentially loneliness at its peak intensity – where it colors your entire worldview. You might start believing thoughts like “No one understands me” or “Everyone else is connected except me,” which are very painful and often not true. In harmful isolation, you also might lose the desire or ability to socialize even if the opportunity arises, due to fear or low self-esteem. It’s as if the door to the outside world is closed and you don’t have the energy to open it, even though deep down you wish someone would come in. If you find yourself in this state, it’s a sign that you need to take action to care for your mental health – whether by reaching out for support, seeing a therapist, or making small changes to break the pattern. Prolonged harmful isolation can be dangerous; humans need some level of connection, and without it, one can spiral into severe depression or hopelessness.

So how can you differentiate which kind of alone time you’re experiencing? Here are a few telltale signs:

- Emotions during alone time: After some time alone, do you feel refreshed, calm, maybe pleasantly introspective? That’s solitude. Or do you feel sad, anxious, agitated, or exhausted? That leans toward harmful isolation. Solitude might come with moments of melancholy (that’s normal), but predominantly you find a stable or positive mood. Isolation is mostly painful emotionally.

- Your attitude toward being alone: If you choose to have an afternoon to yourself, or you find ways to enjoy the day despite being alone, you’re in solitude. If you dread being alone and feel it’s forced on you, it leans toward isolation. Likewise, if you take pride in your independence or see value in it, that’s healthy. If you feel ashamed of being alone or see it as evidence of your “failure,” that’s unhealthy.

- Level of engagement: In healthy solitude, you stay engaged with life – you do activities, you take care of yourself, you maybe set plans for the day. In isolation, you might disengage – e.g. spending hours just scrolling social media with a hollow feeling, or lying in bed doing nothing because you can’t muster motivation. Engagement indicates you’re treating your alone time as life; disengagement suggests you’re in a kind of limbo state, waiting for life to begin when others show up.

- Sense of connection: Paradoxically, solitude can still carry a sense of connection. You might feel connected to your own inner world, or to interests, or to nature, or spiritually connected to humanity in a broad sense. In harmful isolation, you feel disconnected on all fronts – like there’s an invisible wall between you and the world. If you can still empathize with others, feel love toward people or things (even from afar), or feel part of humanity, your solitude isn’t completely isolating you. But if you feel numb or alienated, that’s a warning sign.

- Choice and balance: Healthy solitude is usually interspersed with social interaction here and there. Even introverts who love solitude have some social outlets and generally know they could reach someone if truly in need. Harmful isolation often involves feeling like you have no choice – e.g. “I have no one to call, even if I wanted to.” If you realize you haven’t talked to anyone (or left the house, if applicable) in days and that’s causing you distress, it may be tipping into unhealthy territory.

If you determine that a lot of your alone time has slid into the harmful isolation category, don’t despair. The fact that you recognize this difference is a positive first step. You can then work on gradually shifting your experience back toward healthy solitude. That might involve purposely planning small social interactions to break up long periods of aloneness, or talking to a professional if you feel stuck in negative thoughts. It might also involve revisiting the coping strategies from earlier sections – reigniting hobbies, improving self-care, practicing mindfulness – essentially, re-engaging with yourself and the world in little ways so that your time alone becomes meaningful again, not just empty.

On the other hand, if you’ve found a good rhythm of solitude that feels nourishing, embrace it! Society sometimes pressures people to always be social, but there is nothing wrong with enjoying your own company. Solitude is not “better” or “worse” than socializing – both are valuable, and a healthy life usually has a mix of both. The goal is balance and authenticity. If you’re someone who needs a lot of alone time to recharge and grow, accept that about yourself and don’t let others label it as isolation if you feel content. Conversely, if you’re naturally very social but going through a lonely spell, acknowledge that extended alone time isn’t your ideal and take steps to increase interaction to a healthy level for you. In short, healthy solitude is constructive and chosen, whereas harmful isolation is destructive and often unwanted (Companionship in Solitude with Hopper by Louisa Hutchinson). By staying mindful of how solitude is affecting you, you can adjust and find the sweet spot where being alone is a positive experience.

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

Loneliness is a tough emotion, but it does not have to control your life. By applying practical coping techniques – like nurturing yourself, engaging in fulfilling activities, and practicing mindfulness – you can ease the pain of loneliness. By understanding the psychology of loneliness, you realize it’s a common feeling with causes you can address, rather than a personal failing. Philosophical perspectives from existentialism, Buddhism, Stoicism, and other traditions show that being alone has deeper meaning and value – it can lead to authenticity, enlightenment, inner strength, and creativity. With time, you can build emotional resilience so that you not only withstand loneliness, but actually grow through it. You learn to accept yourself wholly, in quiet hours just as much as in company. You discover that solitude can be rich: it’s a chance to reconnect with who you are, to pursue your passions, and to rest in a noisy world. And you learn the difference between enjoying healthy solitude versus falling into unhealthy isolation, keeping yourself balanced and cared for.

Ultimately, accepting loneliness is about finding peace with your own company. It’s about realizing that you are enough, that your worth isn’t defined by how many friends or social invitations you have. When you come to cherish solitude, loneliness loses much of its sting – being alone no longer feels like a void to be feared, but rather like a canvas on which you can paint your day or a quiet garden where you can tend to your inner thoughts. This shift won’t happen overnight, but step by step, with compassion and practice, it will happen. Remember that you’re not truly alone in feeling lonely; many others are walking that same journey toward self-acceptance through solitude. By choosing to see loneliness as an opportunity for self-discovery, you are turning a painful experience into a profound one. In the silence of your own presence, you may hear the quiet voice of your heart more clearly – guiding you to new understandings and strengths. In time, you might even thank loneliness for what it taught you. Embrace the path of solitude, and you’ll find that accepting loneliness leads to the discovery of a resilient, content, and creative self that was there within you all along.

Sources:

- Utah State University Extension – Coping With Loneliness (Part 1): Look Inward (Coping With Loneliness (Part 1): Look Inward | USU) (Coping With Loneliness (Part 1): Look Inward | USU) (Coping With Loneliness (Part 1): Look Inward | USU) – Definition of loneliness, mindfulness and solitude benefits.

- U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory – Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation (Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation) (Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation) – Research on health impacts of loneliness (equating to smoking risks, links to depression/anxiety).

- Psychology Today – Existential Isolation Is Key to Healthy Relationships (Existential Isolation Is Key to Healthy Relationships | Psychology Today) – Insight from existential psychology that facing aloneness can improve relationships.

- Pema Chödrön (Buddhist teachings) – “Cool Loneliness” (Pema Chödrön’s Six Kinds of Loneliness) (Pema Chödrön’s Six Kinds of Loneliness) – Describing a mindful approach to loneliness, learning to sit with it calmly.

- Manning Hosp. (Child Psychiatry) – Navigating Solitude: Strategies for Overcoming Loneliness (Strategies for navigating loneliness and isolation) (Strategies for navigating loneliness and isolation) – Coping strategies like creative expression and journaling to process feelings.

- Orion Philosophy – How Do Stoics Deal With Loneliness? (How Do Stoics Deal With Lonliness? - Orion Philosophy) (How Do Stoics Deal With Lonliness? - Orion Philosophy) – Stoic viewpoints (Seneca, Epictetus) on being content with one’s own company and focusing on what’s in our control.

- Murthy, V. (2020). Together: The Healing Power of Human Connection in a Sometimes Lonely World – (Referenced in USU Extension) Emphasizes self-compassion and “befriending ourselves” as a foundation before connecting with others (Coping With Loneliness (Part 1): Look Inward | USU).

- Additional wisdom: “Loneliness is the poverty of self; solitude is the richness of self.” – May Sarton (poet) (May Sarton - Loneliness is the poverty of self; solitude...). This quote elegantly captures the difference between the empty feeling of loneliness and the fullness that can be found in solitude. It reminds us that being alone, in itself, isn’t the problem – it’s how we experience it. By working on the strategies and perspectives above, you can turn loneliness into a fruitful solitude, moving from a sense of lack to a sense of richness in your own company. (May Sarton’s words serve as a guiding mantra for this journey.)